Welcome all to this introduction to machine learning (ML). In this session we will:

- Introduce to the general logic of machine learning

- How to generalize?

- The Bias-Variance Tradeoff

- Selecting and tuning ML models

Updated April 16, 2021

Welcome all to this introduction to machine learning (ML). In this session we will:

As with any concept, machine learning may have a slightly different definition, depending on whom you ask. A little compilation of definitions by academics and practioneers alike:

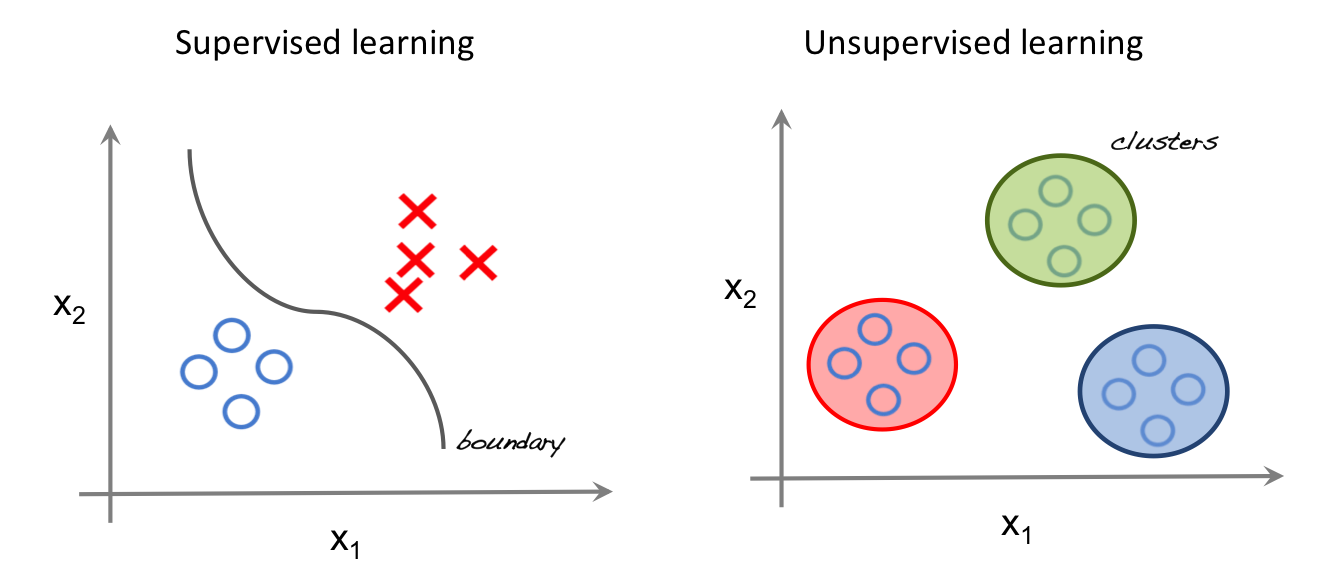

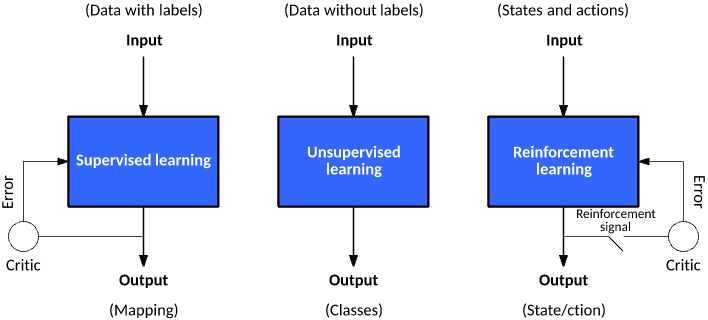

Tasks related to pattern recognition and data exploration, in dase there yet does not exist a right answer or problem structure. Main application

This is what is currently driving >90% ML applications in research, industry, and policy, and will be the focus on the following sessions.

Lets for a second recap linear regression techniques, foremost the common allrounder and workhorse of statistical research since some 100 years.

\[y = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_1 + \beta_2 x_2 + ... + \beta_n x_n + \epsilon \]

| Dependent variable: | |

| y | |

| x | 0.304*** |

| (0.008) | |

| Constant | 14.792*** |

| (0.453) | |

| Observations | 500 |

| Log Likelihood | -1,526.330 |

| Akaike Inf. Crit. | 3,056.661 |

| Note: | p<0.1; p<0.05; p<0.01 |

y based on observed values of x * After the model’s parameters are fitted, we can use it to predict our outcome of interest. * Is here done on the same data, but obviously in most cases more relevant on new data.

\[ RMSE = \sqrt{\frac{1}{n}\Sigma_{i=1}^{n}{\Big(y_i - \hat{y_i} \Big)^2}}\]

Keep in mind, this root&squared thingy does nothing with the error term except of transforming negative to positive values.

## [1] 5.112672

## # A tibble: 6 x 2 ## x y ## <dbl> <int> ## 1 1.33 1 ## 2 1.43 1 ## 3 -1.73 0 ## 4 -1.24 0 ## 5 0.196 1 ## 6 -1.03 0

probability: y=TRUE| Dependent variable: | |

| y | |

| x | 4.977*** |

| (0.489) | |

| Constant | -0.085 |

| (0.170) | |

| Observations | 500 |

| Log Likelihood | -113.223 |

| Akaike Inf. Crit. | 230.447 |

| Note: | p<0.1; p<0.05; p<0.01 |

glm, where we just change the distribution from gaussian to binomial

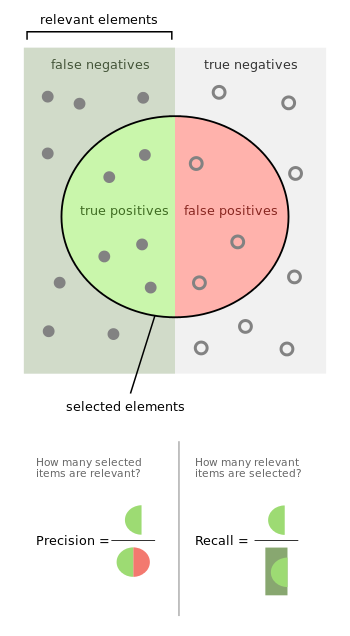

It is the 2x2 matrix with the following cells:

True Positive: (TP): You predicted positive and it’s true.

True Negative: (TN)

False Positive: (FP) - (Type 1 Error): You predicted positive and it’s false.

False Negative: (FN) - (Type 2 Error): You predicted negative and it’s false.

Just remember, We describe predicted values as Positive and Negative and actual values as True and False.

Out of combinations of these values, we dan derive a set of different quality measures.

The simplest one is the models accuracy, the share of correct predictions in all predictions

Accuracy (ACC)

\[ {ACC} ={\frac {\mathrm {TP} + \mathrm {TN} }{P+N}} \]

Sensitivity also called recall, hit rate, or true positive rate (TPR) \[ {TPR} ={\frac {\mathrm {TP} }{P}}={\frac {\mathrm {TP} }{\mathrm {TP} +\mathrm {FN} }}\]

Specificity, also called selectivity or true negative rate (TNR) \[ {TNR} ={\frac {\mathrm {TN} }{N}}={\frac {\mathrm {TN} }{\mathrm {TN} +\mathrm {FP} }}\]

Precision, also called positive predictive value (PPV) \[ {PPV} ={\frac {\mathrm {TP} }{\mathrm {TP} +\mathrm {FP} }} \]

F1 score: weighted average of the true positive rate (recall) and precision. \[ F_{1}={\frac {2\mathrm {TP} }{2\mathrm {TP} +\mathrm {FP} +\mathrm {FN} }} \]

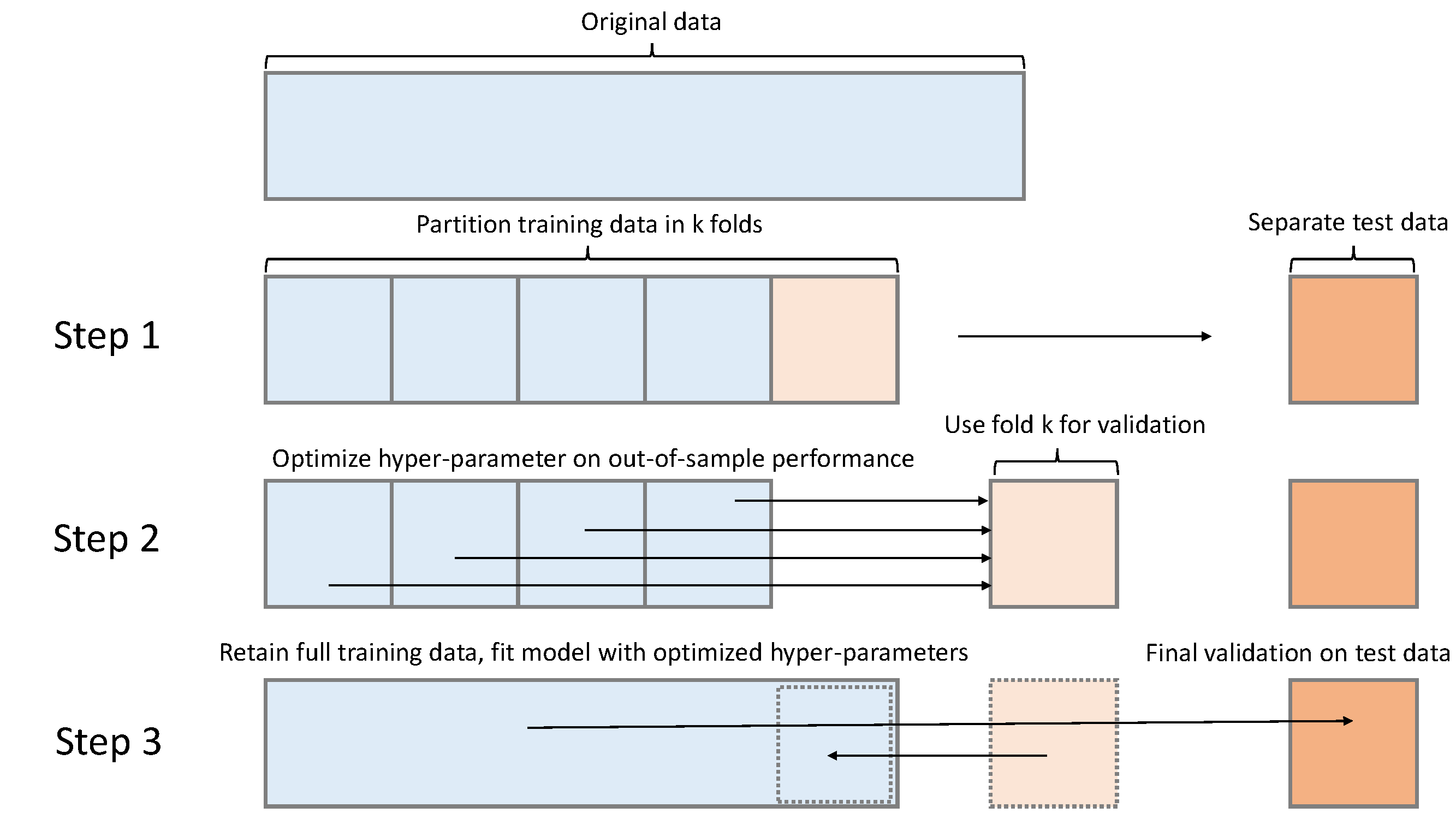

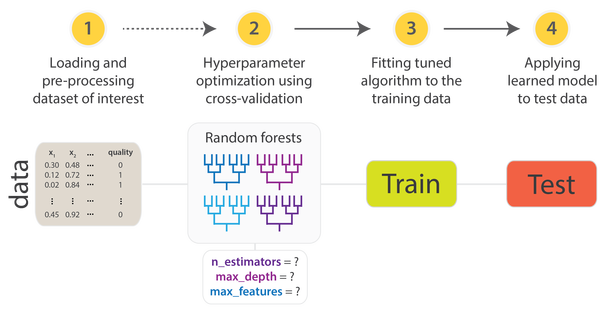

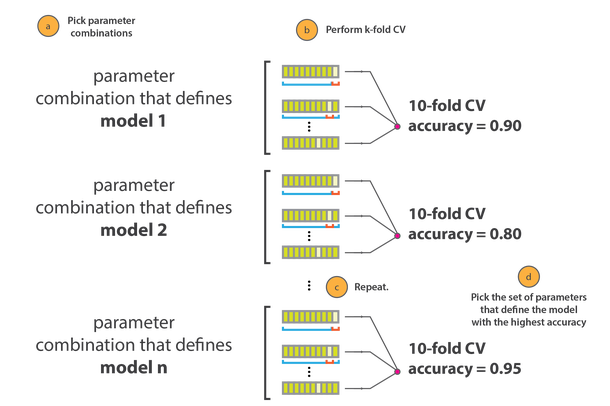

An advanced version is a N-fold-Crossvalidation, where this process is repeated several time during the hyperparameter-tuning phase.

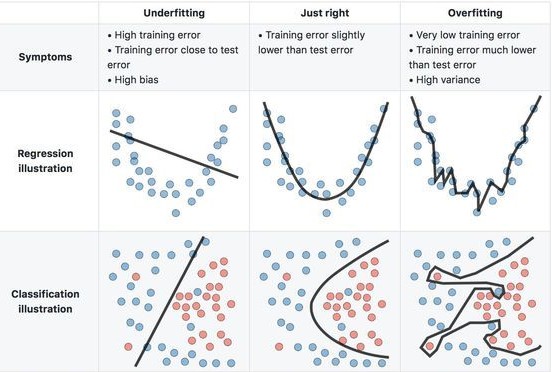

Generally, we call this tension the bias-variance tradeoff, which we can decompose in the two components:

\[{\displaystyle \operatorname {E} {\Big [}{\big (}y-{\hat {f}}(x){\big )}^{2}{\Big ]}={\Big (}\operatorname {Bias} {\big [}{\hat {f}}(x){\big ]}{\Big )}^{2}+\operatorname {Var} {\big [}{\hat {f}}(x){\big ]}+\sigma ^{2}}\]

Note:

Lets see how models with different levels of complexity would interpret the reælationship between \(x\) and \(y\):

Mathematically speaking, we try to minimize a loss function \(L(.)\) (eg. RMSE) the following problem:

\[minimize \underbrace{\sum_{i=1}^{n}L(f(x_i),y_i),}_{in-sample~loss} ~ over \overbrace{~ f \in F ~}^{function~class} subject~to \underbrace{~ R(f) \leq c.}_{complexity~restriction}\]

Also formerly trending…

The elastic net has the functional form of a generalized linear model, plus an adittional term \(\lambda\) a parameter which penalizes the coefficient by its contribution to the models loss in the form of:

\[\lambda \sum_{p=1}^{P} [ 1 - \alpha |\beta_p| + \alpha |\beta_p|^2]\]

This class became increasingly popular in business and other applications. Some reasons are:

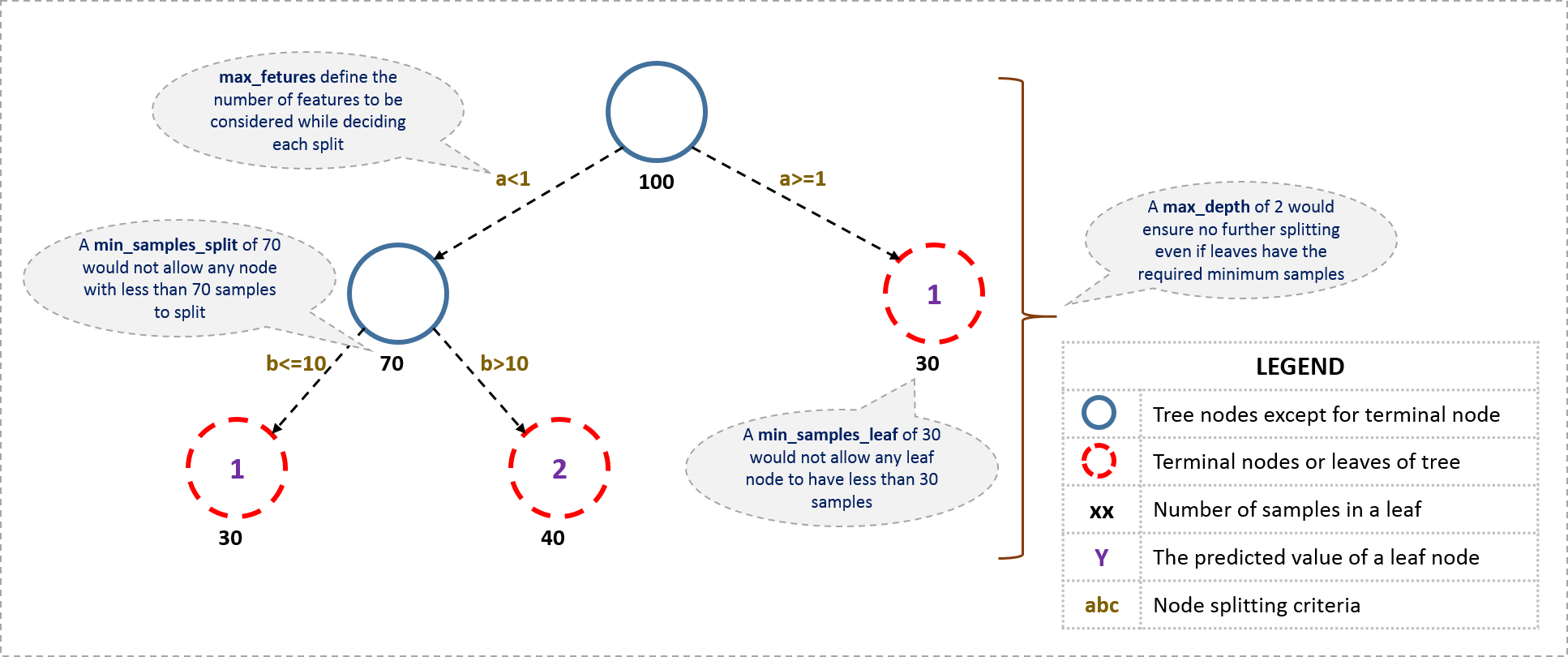

The decision of making strategic splits heavily affects a tree’s accuracy. So, How does the tree decide to split? This is different across the large family of tree-like models. Common approaches:

Some common complexity restrictions are:

Likewise, there are a variety of tunable hyperparameters across different applications of this model family.

In this session, took a look at

In the next sessions, we will apply what we learned so far… so stay tuned!